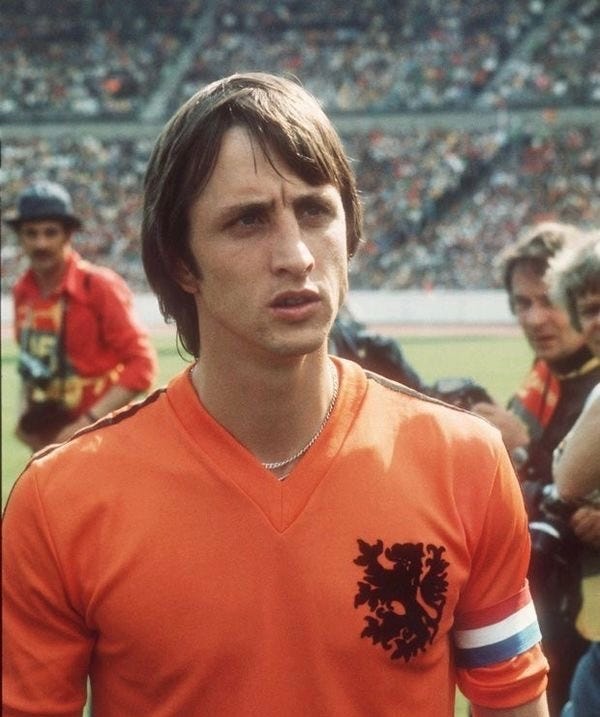

In the late seventies, Johan Cruyff stood at the edge of football immortality. The Dutchman was the face of a new era, an architect of Total Football and the proud owner of three Ballon d’Ors. Cruyff had played a major role in redefining the way football was played, bringing flair, fluidity and finesse from Amsterdam and Barcelona to the world stage.

But at 1977’s Ballon d’Or ceremony, when the envelope was opened, it wasn’t Cruyff’s name that was read out. It was that of Allan Simonsen, an understated Danish forward from West German champions Borussia Mönchengladbach.

The football world was stunned. Simonsen was a top class player but was he the same calibre as Cruyff? The answer wasn’t that straightforward.

To understand how Johan Cruyff, the golden boy of European football, was snubbed, let’s rewind to his messy divorce with Ajax. By 77, Cruyff was a legend in Amsterdam, having led de Godenzonen to three consecutive European Cups and transformed the team into a force to be reckoned with.

But as his stardom grew, so did the tension. Cruyff was not one to kerp his head down. The Amsterdammer was outspoken, critical and didn’t think twice about challenging management. He argued tactical decisions, wages and the club’s treatment of its players. Then, a changing room brawl that proved to be the final straw.

Cruyff was out. He upped sticks to Barcelona, bringing his unique talent and personality to the Catalan coast, where he continued to impress. But some in the Netherlands were left feeling betrayed. Cruyff had abandoned his team in the most public of ways. He was a generational talent beyond doubt, but also a troublemaker, and a headstrong individual who didn’t fit the mould of the typical star.

Just as the Dutch national team was preparing to head to South America for the 1978 World Cup, Cruyff made another shock decision. He was retiring from international football. This was the talisman who had led Holland to the 1974 World Cup final, the maestro behind the Oranje’s brave new style that had fascinated fans everywhere.

Dutch supporters were stunned. Some claimed Cruyff’s wife disliked the pressure of international tournaments. Others claimed he feared for his family’s safety after a recent break-in. Whatever the true reason, his departure was seen by many as yet another act of dereliction, and it was not appreciated.

In the eyes of Ballon d’Or voters, Cruyff had, perhaps, gone too far. He was brilliant on the pitch but seen as a maverick off it. While he was still revered by many, others were more hesitant.

Enter Mr Simonsen. Mönchengladbach’s man was skillful and industrious, but had a name few expected to hear in the Ballon d’Or conversation. Yet in 77, Simonsen turned heads with performances in the UEFA Cup, leading the foals to glory by scoring crucial goals in both the semi-final and final.

Where Cruyff was flair and arrogance, Simonsen was grit and humility. He didn’t demand the spotlight or speak out against authority. He was essentially the anti-Cruyff.

By handing Simonsen the Ballon d’Or, France Football made a clear statement: the best player in the world didn’t need to be a revolutionary; he could be a steady performer. For the establishment, Simonsen’s win was viewed as a return to football’s humble roots.

For Cruyff, the snub was more than a professional setback; it was a personal attack. In the years to come, he would channel that energy into his role as a manager, further revolutionising football. Simonsen, meanwhile, would be remembered as one of the Ballon d’Or’s most understated winners - a hard-working attacker who represented football’s ideals.